Read Me Like A Feed

What story is your digital self telling?

Whenever I leave my apartment, I put on old seasons of RuPaul’s Drag Race for my Boston terrier, Five. I turn the volume up before I go, loud enough to block out the common hallway noises that used to make him bark, even though I know Five can’t hear anything. He’s fifteen, completely deaf, and starting to lose his vision.

I like to think that the blurry drag queens bickering on screen keep him company during the long silences that punctuate my leaving and returning home. A few days ago, I came back from the gym and found Five asleep on the couch, the television still glowing. RuPaul was mid-sentence, offering advice to a young queen struggling with being on camera. The queen protested, they usually do, but this time RuPaul wasn’t having it.

“You’re trying to control how people see you,” he said. “I don’t have time to do that. I’m too busy living my goddamn life!”

Normally, Drag Race is just background noise. But this stopped me. I wrote it down. What surprised me wasn’t that it resonated, but that it irritated me. By saying this on camera, wasn’t RuPaul doing exactly what he claimed not to care about? Wasn’t this, too, a way of controlling how people see you?

I stood there for a moment, half-unzipped gym bag at my feet, sweaty shirt stuck to my back, listening to RuPaul talk about authenticity and freedom and not giving a fuck what anyone thinks.

In the past, his advice had always felt like it was aimed at someone else: drag queens, influencers, people chasing attention and a spotlight. After I left my reality show, I didn’t want to be the story anymore. I was careful to shift the focus back onto my films, onto the work. But somewhere along the way, I stopped managing how I came across online altogether.

For years, I told myself that opting out of social media meant opting out of that entire economy of attention. That whatever was happening on those screens—visibility, self-presentation, performance, control—wasn’t about me.

That belief (mostly) held until two collaborators messaged me about another filmmaker earlier this week. Someone whose name had started to travel quietly, the way these things do. The messages were carefully coded: nothing that could be forwarded or screenshot, with just enough details to reveal a personality type I’d definitely encountered on set before.

I did what we all do now. I went to their Instagram and started scrolling. Not casually, but methodically, treating this person’s profile like it was a personnel file. What story are they telling about themselves? How are they presenting themselves visually? What’s missing? And does any of it line up with what I’d been told?

It was only after I closed the app that something else finally registered, a colder realization, arriving years too late: this is probably how other people in the industry look at me online, too.

I used to think social media was for influencers, for people who wanted to be watched. Scrolling through other people’s curated lives usually made me feel worse about my own, so I stopped. I told myself this was healthy, that opting out was a kind of integrity. After all, it wasn’t a full boycott. I just didn’t believe this was a place where serious storytelling happened.

Yet here I am, working in a visual industry, one where image is routinely used to construct both identity and meaning. Why hadn’t it ever occurred to me that treating my own online presence as an afterthought might be telling a story, too?

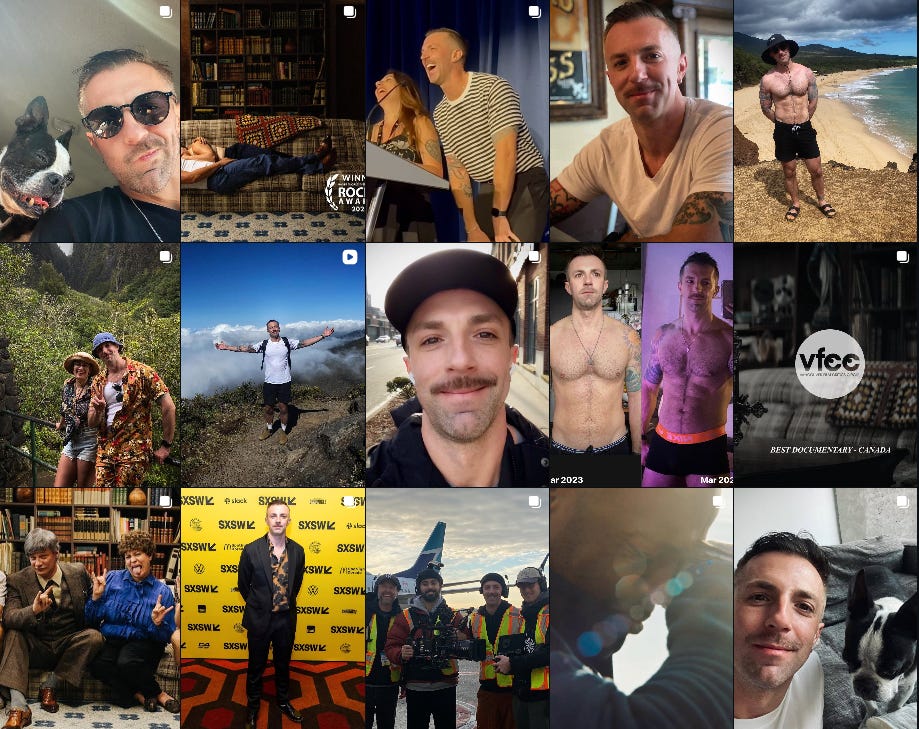

Two weeks ago, I wrote about taking my shirt off for a magazine and the complicated relationship I’ve always had between my body and my career. But after picking apart another filmmaker’s Instagram, I went back and looked at my own, and realized that story wasn’t finished with me yet.

About two years ago, around the time I became single again after a long relationship, something began to shift in what I posted online. What had once been a fairly coherent professional portfolio on Instagram—film festivals, reviews, trailers, the kind of account you scroll past and think, Does this man even have a personality?—splintered into something harder to read. Vacation photos appeared beside movie posters and press stills. Fitness updates jostled for space with Substack links, commercials I’d directed, old clips from my reality show.

The effect wasn’t evolution so much as accumulation of parts visually stitched together into some digital Franken-monster: HDR iPhone videos next to film trailers; a self-serious director portrait followed immediately by an oversaturated beach photo; a stark text quote beside a sit-down interview frame with entirely different lighting logic. Plenty of substance, scattered everywhere. No style strong enough to hold any of it in place.

And of course, this most recent return of shirtlessness, doing its familiar and dependable work.

Maybe I’ve been looking at this the wrong way. It’s not only about being seen, but also deciding how. After a breakup, a career stall, or some other losses, the body rushes in to fill the gap. The body is immediate. It’s readable. It doesn’t require context or backstory. Online, this manifests in the gym mirror or the vacation pool, a carefully casual shirtless photo taken at exactly the right angle.

I’m still here, the image seems to say. Do you see me?

A few other essays that are part of this conversation: